Key featured species

- Common Whitethroat communis

- Lesser Whitethroat Sylvia curruca

The problem

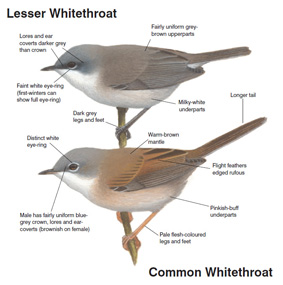

Both whitethroats arrive in numbers around the third week of April. They share the key feature that gives them their name and can appear similar at a glance, so familiarity with their distinguishing characters is useful.

Click here for larger image. Illustration by Ren Hathaway.

The solutions

Common Whitethroat

Despite a catastrophic 80 per cent crash in its population during the winter of 1968-69, which was caused by a severe drought in the Sahel region of West Africa, Common Whitethroat is still much the more numerous of the two whitethroats. It occurs throughout Britain, whereas Lesser Whitethroat breeds mainly in central and southern England, being rare in the north and extreme west.

Apart from the differences in their range, the first clue to their identification is habitat. Common Whitethroat is a bird of low, open, bushy and scrubby areas, particularly where there are brambles, and also in bracken, tall weeds and low hedgerows. Reflecting its choice of habitat, it tends to keep low and it can often be flushed from tall weeds, flitting into cover ahead of the observer with a jaunty flicking of its rather long, square-ended tail. Narrow white outer tail feathers are both obvious and distinctive.

At rest, the key feature to look for is the rusty fringing to all the wing feathers, producing a conspicuous rusty panel on the closed wing. The underparts vary from pinkish (males) to buffish (females) but, as the name suggests, they always contrast strongly with the prominent white throat. The mantle, back and scapulars are a rather drab brown. On females, the head is the same colour, but on males it is contrastingly grey. Both sexes show a narrow white eyering, which is stronger on males. Unlike Lesser Whitethroat, both the legs and the base of the lower mandible are pale, varying from yellowy through flesh to horn.

The easiest way to locate a Common Whitethroat is by song and call but, having said that, the song is virtually indescribable! Uttered in bursts lasting 3-4 seconds, it is sweet, throaty and scratchy almost all at the same time, and is very distinctive once learned. It often accompanies a jerky display flight, a facet of the species’ lively, impetuous and extrovert character. Rising to a height of up to 10 m, the bird raises its crown and spreads its tail before descending – with exaggerated wing beats – in a series of jerky swoops (Cramp 1992).

The calls are similarly distinctive, the most frequently heard being a low, deep churr or occasionally churrit, and an angry, scolding, hoarse but slightly nasal vid vid vid vid vid ….The birds often give such calls when they have fledged young, berating the observer, with their white throat feathers fluffed out to produce a distinctive ‘jowled’ effect.

Lesser Whitethroat

The common feature of Lesser and Common Whitethroats is, not surprisingly, a white throat; the important difference is that Lesser’s entire underparts are a smooth, silky white. These contrast with distinctively toned grey-brown upperparts and a grey head, which is slightly darker on the lores and ear coverts. Unlike Common Whitethroat, there are no rusty fringes to the wing feathers, which are instead finely fringed with grey-brown, appearing rather uniform at any distance. Also unlike Common, it lacks an obvious eyering and both the bill and legs are dark; the latter grey in good light.

In a flight view, Lesser Whitethroat looks a more compact bird than Common, lacking the latter’s rather long, mobile tail. As it dives into a thick hedgerow, it appears essentially grey above with narrow white outer tail feathers. When settled, it is the smart contrast between the greyish upperparts and clean-looking silky white underparts that allows easy recognition.

Unlike Common Whitethroat, Lesser is a real introvert and even newly arrived songsters can be frustratingly difficult to see. They prefer taller, thicker hedges, often singing from deep inside hawthorns and blackthorns, remaining well hidden in the dense tangle of twigs and branches. In late summer and autumn, however, juveniles and first-winters become quite easy to see as they fatten up in willows prior to migrating, often roaming around with mixed flocks of tits and other warblers.

Lesser Whitethroat’s song is completely different from that of Common Whitethroat, but is also very difficult to describe. Traditionally termed a ‘rattle’, it is actually more of a relatively short but far-carrying one-noted rhythmic burst – j-j-j-j-j-j-j-jut – with a deep, rather hollow and almost ringing quality. At close range, it is introduced by a quiet, disjointed warble that sounds high-pitched, thin and scratchy. The call is distinctive, but only with practice. It is a very abrupt, dry ‘tutting’ – cht or st – that is most similar to the call of Sedge Warbler, but even more abrupt. It can also be confused with the call of Blackcap, but that species has a fuller, more deliberate chack than the clipped note of Lesser Whitethroat. The call is very useful in locating birds in late summer and autumn, and once you have learned it you realise that Lesser Whitethroat is much more common than you thought.

Ageing

When adults have completed their late summer moult and juveniles their body moult, ageing and sexing of both species become difficult, but the white outer tail feathers of first-winters are sullied with brown and their eyes are darker than those of adults. First-winter Common Whitethroats also have more diffuse dark centres to their greater coverts.

Migration

As a final point of interest, there is a marked difference in the migration strategies of the two whitethroats. Whereas British Common Whitethroats have a conventional north-south migration to and from West Africa, the entire Western European population of Lesser Whitethroat migrates through and around the eastern Mediterranean to wintering grounds in north-east Africa, mainly in Sudan and Chad. It’s amazing to think that some of the Lesser Whitethroats that migrate through the Middle East end up singing from hedgerows in southern England.

More than one species?

There are several races of Lesser Whitethroat, the most frequent extralimital form that occurs in Britain being blythi from Siberia. However, this form is now generally considered synonymous with the nominate curruca that breeds in Britain and the rest of Western Europe. Other races in Asia include minula and halimodendri, both of which have been identified in Britain in late autumn and/or winter. Indeed, the occasional wintering bird is perhaps more likely to be of an extralimital Asian race than one of our own nominate curruca, so any out-of-season individuals should be scrutinised very carefully; ideally, they will be trapped and feathers taken for DNA analysis.

It has been suggested that the Lesser Whitethroat complex should be split into perhaps two or three species. However, while many forms appear reasonably distinct, it may prove to be a ‘ring species’, where different ends of the ring appear to be good species but, in between, the various forms merge seamlessly into each other. They currently remain lumped, pending ongoing research.

Reference

- Cramp, S (ed). 1992. The Birds of the Western Palearctic.Vol VI. Oxford University Press, Oxford.